How the fight against non-physical violence is being hindered

The lack of trust in constituted authorities, a culture of silence, and an underfunded law enforcement system continue to undermine efforts aiming to bring an end to the under-reported issue of non-physical violence. In this report, FRANSISCA OGAR, ANIBE IDAJILI, JULIET BUNA, MELONY ISHOLA and NCHETACHI CHUKWUAJAH assessed the extent to which these constraints are risk factors for non-physical violence against women. More than 60 female journalists completed a cross-sectional survey on non-physical violence in newsrooms. 78% of the respondents reported at least two incidents of non-physical violence while formal complaints of abuse suffered were made by only 26% of respondents. Through our findings, we argue that filing reports, enforcing consequences for perpetrators, implementing a zero tolerance policy, and effectively modifying cultures of violence are key to overcoming the hindrances to the fight against non-physical violence against women and girls.

*The names of the survivors have been changed for their safety.*

Who would have thought that speaking mere words to a person, isolating them from family and friends, or preventing them from earning a living because as a man you need them to be full-time housewives, could be deadly?

For Kebbi-based Fatima Usman, the hardest thing about being married to a manipulative, uncaring partner is the mental and emotional exhaustion. Since they got married ten years ago, he has alternated between making demeaning jokes about her and treating her like a crazy person. For the mother of four, it is a never-ending circle. To this day, Fatima is unable to pinpoint what triggers her husband’s abusive episodes.

“Sometimes, I cry from 6:00 PM to 6:00 AM. I might appear to be happy, but on the inside, I am dying. I have never told anyone about what I am going through, not even my parents. No one will believe me. He is respected in the community and seen as a good man,” says 42-year old Fatima, who is a graduate of Chemical Engineering.

It is easy to assume that the majority of people who experience non-physical abuse are poor and illiterate. However, there are many accounts of abuse, directed against educated and employable women like Fatima.

The 2013 Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey on the relationship between occupation and women’s experience of intimate partner violence, which was a nationally representative sample of 38,948 women and 17,359 men aged 15–49, shows that women in occupations of similar rank to their partners were twice as likely to experience physical and emotional violence, compared to women ranked lower than their partners. In the survey, professional women were the next most likely to experience emotional abuse.

Abusive bosses and colleagues

Thinking she had found a “veteran” mentor, Joana Moses, who had just assumed a new role as a radio host at a broadcast station in Minna, Niger State, made sure to take note of everything her boss said as professional guidance. She was determined to give this job her best. This job was a step toward attaining her goal of becoming a big shot in journalism. But this was before her new boss—male– began grooming her by sharing “secrets” to reel her closer.

“At first, it seemed normal. Then he suggested taking me to his apartment “just to pick something up,” Moses said.

She had thought nothing of it when he suggested “special coaching” sessions and agreed to initial meetings. However, the “unintended touches” became groping as the weeks passed. After only four months, unable to deal with the abuse, she quit her job, and her dreams of a media career took a huge blow.

When issues of abuse are discussed, non-physical abuse is at the bottom of the consideration; however, research shows that women, especially female professionals, are the most likely to experience emotional abuse in the workplace. In the Nigerian media–primarily male-dominated– female journalists like Moses experience workplace abuse daily.

“I blamed myself for a long time,” Moses said. Until now, she never told anyone about what had transpired between her and her boss. “After all, there was this other lady he claimed to be mentoring, and I don’t remember anyone saying anything about her being abused,” she said.

Her boss’s bosses would never have believed her, she said.

Many female journalists who wished to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal said male bosses or colleagues initially supported them but later made the job frustrating when they refused their sexual advances.

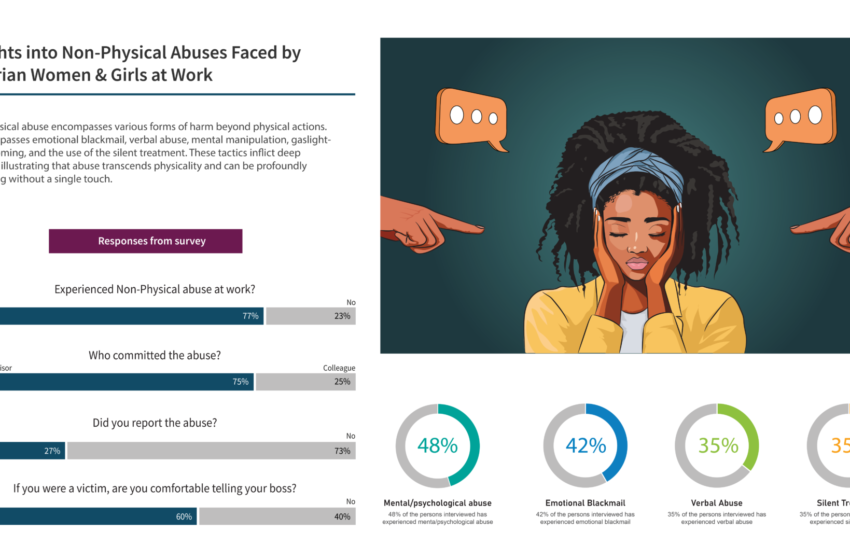

In a survey of female journalists in over 20 newsrooms in Nigeria, including freelance journalists, 62 journalists said they had experienced at least two of the non-physical kinds of abuse, which include gaslighting, silent treatment, verbal abuse, mental abuse, emotional blackmail, and grooming. The highest prevalence rate was seen in cases of mental and psychological abuse, and the top perpetrators were supervisors.

One of the respondents, Nusaiba Abba, is an Abuja-based TV anchor with less than five years of experience. She was subjected to offensive, sexually explicit emails and messages from three male colleagues, as well as silent treatment, excessive texting, and mental and psychological abuse. The abusers were never punished despite her reporting the incidents to her supervisor. The TV station did not have a gender equality and social inclusion policy.

“I was told to ignore the people and report if further advances were made. I blocked the three men on social media and on my phone, and made sure I avoided them throughout the six months I worked there. Now they are out of my way.”

So, while they wrote stories of victims abused and called attention to abuse, female journalists endured abuse.

Paper tiger

In 2015, the government enacted the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act to provide succour for survivors, the penalties, and a punitive tool for offenders. Victims of abuse in the workplace are typically advised to report cases of violence or intimidation to trade unions and the police. But with the abusers running operations at the helm of affairs, the police have been of little or no help.

Rita Oyetare, the Deputy Commissioner of Police for Gender at the Nigeria Police Force Criminal Investigation Department (FCID), said the police try to adhere to the VAPP Act and ensure that those who violate it receive the appropriate penalties. However, Oyetare acknowledged that “Emotional, financial, and verbal abuse are all crimes. The Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act partially addresses non-physical violence,” she said.

The Nigeria police is marked with a history of unethical, corrupt, and unlawful actions and with a rather- slow judicial process; in most instances, victims have been forced to settle out of court with their offenders.

For example, “In 2021, only 11 people had been prosecuted out of the over 3,000 cases of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) that had been reported in six states. Of all the cases that were documented, 107 resulted in the abuser or victim’s death, 742 remained unresolved, and 188 were closed,” said Mrs Pauline Tallen, former Minister of Women’s Affairs.

While Oyetare said, “No case is treated as trivial,” and the police try to adhere to the VAPP Act and ensure that those who violate it receive the appropriate penalties, with very situations where the law enforcement agency advised a survivor to settle peaceful abusers, there are still gaps in their access to justice.

“Every Nigerian is aware that from the time they go into a police station to register a complaint until their case is taken before a judge, they are required to pay the police. How many abused women can afford that?” said Halima Musa, a social worker in Niger state.

Evidence and Justice

According to the United Nations, violence against women has taken an alarming dimension both at home and in workplaces. In cases of non-physical abuse, the challenge with a conviction is always the evidence, experts said.

“Many survivors may bear the marks of abuse, but the signs of abuse are never as clear for those experiencing non-physical violence,” said Ijeoma Amugo, NAPTIP Gender Officer.

Even with numerous complaints of non-physical abuse, Hadiza Maman Danstoro, Director, Gender-Based Violence Department Ministry of Justice, Niger, also agreed that the lack of evidence that substantiates claims of abuse has stalled many cases. “What evidence are survivors expected to provide?” remarked Danstoro rhetorically. The gender advocate said lack of empowerment was also a factor that besieged females in professional settings.

Bukola Ashagidigbi, a lawyer based in Ibadan, Oyo State, stressed that the burden of proof in cases of non-physical abuses and lengthy period of cases in court are some of the reasons that stall prosecution of cases of non-physical abuses.

Ashagidigbi adds that, “The non-domestication of the VAPP Act by all states in Nigeria affects prosecution of cases to a great extent. You have to rely on the provisions of each of the states in which you intend to prosecute. So, if the provision in a particular state does not adequately provide for such prosecution, then the extent of the prosecution will be limited to the provision. The judges can only adjudicate within their powers and within the provision of the law. If it is a state law, within the provision of the state and with regards to federal law, the Federal High Court will only make provisions as provided within its laws. For laws extending outside that, it may be difficult for them to prosecute judiciously.”

In the event that a non-physical violence case is established during an inquiry, section 14 (1) of the VAPP Act provides that: “A person who causes emotional, verbal and psychological abuse on another commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of imprisonment not exceeding 1 year or a fine of N200,000.00 or both.”

However, several other laws that seem to legitimise various aspects of domestic abuse have undermined this clause. For instance, beating a wife for “correctional purposes” is permitted under Section 55(1) of the Penal Code, which is applicable in Northern Nigeria.

Another example is the Cross River State Domestic Violence and Maltreatment of Widows (Prohibition) Law, which defines domestic violence to cover any ‘abusive use of physical force or energy to cause damage or injury to a woman at home, in the house or any other place’. The problem with this definition of domestic violence is that it leaves out forms of gender-based violence that are not physical, such as financial, emotional, and verbal abuse.

To curtail the surge in GBV cases across Nigeria, 34 states as well as the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) have domesticated the Violence Against Persons Prohibition (VAPP) Act 2015. Research reveals that while NAPTIP also has an active mandate in the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), in other states, the agency mostly collaborates with relevant stakeholders to increase public awareness and address GBV issues.

Underfunded and untraceable investments

In addition to the fact that it is difficult to find reliable data on the amount of investment for combating GBV, available funding for violence against women and girls in Nigeria does not match the severity of the problem.

State parties are urged to allocate sufficient funds in their government budgets for their efforts to end violence against women in accordance with Article 4(h) of the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. Yet, as evidenced in the 2023 annual budget, only N60.1 million was proposed by the Federal Ministry of Women Affairs for women’s rights and social justice. There is also no mention of the agencies tasked with tackling gender-based violence through policy implementation, protection, and prevention.

International organizations, non-governmental organizations, and private individuals provide the majority of the resources that are available to reduce gender-based violence.

There may be a budget for handling GBV cases for the Nigerian Police, according to a report by Cleen Foundation on the level of awareness and handling of SGBV cases, but it appears to be shrouded in secrecy, which could allow for fund mismanagement and theft.

Muzzled voices

Out of the 62 female journalists who participated in our survey, only 14 filed a formal complaint against their abusers, according to survey responses. The reasons offered by the other 48 for not reporting varied, ranging from a lack of physical evidence to a lack of trust in the authorities to fear about the outcome, further abuse, and even job loss.

Also, in an effort to secure justice for Kebbi-based survivor Fatima Usman, a member of this reporting team dialed NAPTIP’s short code (627). A representative advised that Fatima should file a complaint with the State’s Ministry of Women Affairs or go to the agency’s Kebbi State Command, located at No. 1 Patrick Aziza Road, Birnin Kebbi. She chose the first option.

At the Ministry of Women Affairs, Hajia Maimunat Abdullahi, the Director of Women Affairs, recommended counseling for Fatima and her husband. But she also cautioned that many women like Fatima are aware that the abuse they experience is a problem. Still, addressing the issue may be challenging because they are pressured by their families, religious leaders, or traditional rulers not to tell anyone.

“Under the guise of religion or traditions, some abusers force their partners to put up with non-physical abuse. For this reason, we run awareness campaigns aimed at traditional leaders, religious leaders, survivors, and other relevant stakeholders in the state’s 21 Local Government Areas,” says Hajia Abdullahi.

Regrettably, true to Hajia Abdullahi’s words and despite several pleas and words of support, Fatima got cold feet. Her husband had convinced her that their Imam (Islamic leader), not outsiders, was the best person to help manage their marital problems.

Sometimes, efforts to get justice for survivors are hampered by the culture of silence as well as traditions and religious beliefs, said Dupe Awosemusi, Coordinator of the Oyo State Sexual and Gender-Based Violence Response Team and Referral Centre, like in the case of Moses and Fatima.

“Some of the survivors when they come and we decide to take steps to seek justice, they turn around to say they want to report the cases themselves and they begin to beg on behalf of the perpetrator. So, sometimes before taking some drastic step towards getting justice for survivors, these are some of the challenges we face. I can count a number of cases that we have filed in court and they have refused to turn up to give evidence and when you are short of evidence in any matter in court, the case is dead on arrival.”

“We are trying to break the culture of silence. When people reported such crimes in the past, the police would say, Oh, it’s a family affair. Go home and settle. This isn’t the case anymore. Gender-based violence concerns have advanced to the point where nothing is taken for granted anymore. These cases—no matter how minor—are handled properly,” said Oyetare.

Similarly, Barrister Maryam Lawal, gender desk officer for the Kebbi State Ministry of Justice, said reluctance from victims to speak up or provide evidence are some of the reasons why the state has dropped cases before plea. With fear as a primary reason for silence, regrettably, “Some survivors have become suicidal and may even be capable of murder because of suppressed feelings of resentment toward their abusers,” said Lawal.

However, the absence of efforts in the health sector for survivors of non-physical violence and crucial platforms linking survivors to help and care services may be the biggest hindrance yet.

Amugo, at NAPTIP, said a major step toward ending the culture of silence would be to provide safe shelters across states and provide sufficient funds for all stakeholders advocating for the end to non-physical violence.

“The good news is that survivors do not need money to get a lawyer to take up their cases because the International Federation of Women Lawyers (FIDA) provides pro bono services,” said Lawal, who is also a member of FIDA.

There is need for psychosocial support, according to Titilola Vivour-Adeniyi, the pioneer Executive Secretary of the Lagos State Domestic and Sexual Violence Agency, especially for women suffering non-physical violence who were raised in environments that normalized the actions of their abusers.

While the survey showed that most female journalist respondents and women abused by their partners would be open to calling out their abusers or taking legal steps against them, it is unclear what justice means to the dozens of women we spoke to. Whatever that means, is it enough compensation for lost time, opportunity, and, in some instances, family and friends? Is it even healing for the mental traumas?

This report was produced as part of the African Women in Media (AWiM) Reporting Violence Against Women and Girls project