Suicidal and capable of murder: The women stuck in non-physical violence

The effects of non-physical abuse against women and girls are far-reaching.

Non-physical abuse against women and girls is one aspect of abuse that is hardly talked about in the Nigerian society for many reasons including the burden of proof for survivors, culture of silence and societal dismissal of its impact. In this first of a two-part report, FRANSISCA OGAR, ANIBE IDAJILI, JULIET BUNA, MELONY ISHOLA and NCHETACHI CHUKWUAJAH, write that while the Nigerian society shy away from talking about it, victims and survivors of non-physical abuses are a shadow of themselves and might be contemplating suicide.

*The names of the survivors have been changed for their safety.

Winifred Chioma (not real name) goes about her day with a cheerful, wide and welcoming smile, and a gait characteristic of someone who knows her purpose.

Nothing in the appearance of Winifred, an entrepreneur, portrays that she has contemplated suicide twice and lives with a deep-seated scar owing to the non-physical abuse she suffered in the hands of her husband of many years including manipulation, gas-lighting and trash-talking.

The young lady in her late 20s said the abuse she suffered took a toll on her self-esteem and made her doubt herself afterwards until a member of her church offered her help.

“My case was a very pathetic and typical one because I lost my Mum and we didn’t have a father figure with us. After my Mum’s death, we just started living our lives. So, it was very easy for the abuser to take advantage of that situation.

“At first, he tried to be a friend; someone that will be there, someone that will always give me a listening ear so I could feel free to confide in him but in the long run, the true nature of his motive, gradually began to unfold. He didn’t have to work so hard isolating me from my family because already, I didn’t have any family at all,” she said.

Odochi (not real name) lost her husband and all five of her children in adulthood. Since then, her husband’s family demanded she leave their family since she has no one left. She said they have deprived her of her husband’s inheritance and left her without a means of livelihood. Added to this are daily ridicule and threats to kill her if she doesn’t leave the family.

Odochi says she barely eats and depends on the benevolence of neighbours as she has nothing to fall back on.

“Marriage brought me here and I gave birth to five children, both male and female here but I have none today,” she said in Igbo.

“My husband’s kinsmen have stripped me of everything, left me empty-handed, yet keep threatening to kill me unless I return to my father’s house.

“I attend a church so I have taken it to God who owns heaven and the earth and He has said I shouldn’t go anywhere but remain here,” she added in a voice nearing tears.

Odochi may not remember how old she is, but the constant verbal reminders of her childlessness and deprivation of her rights by her in-laws are permanently etched in her memory.

A national menace?

Like Winifred and Odochi, 68 percent of Nigerian women aged between 15 and 49 years had experienced varying degrees and types of abuses that are not physical such as emotional, economic or sexual abuse compared to 30 percent of women who had experience physical violence, according to a 2020 survey by the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS).

The survey also found that overall prevalence of spousal physical or sexual or emotional violence increased from 24.5 percent in 2013 to 36.2 percent in 2018.

In the ‘Women and men attitude towards domestic violence’ section, the survey states “Some women and men in Nigeria believe that a husband is justified in beating his wife if she does the following: she goes out without telling him, she neglects the children, she argues with him, she refuses sex with him, or she burns the food.”

In November 2023, the Data Manager, Federal Ministry of Women Affairs, Sunday Agbakaba, said Nigeria recorded 27,698 cases of Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (SGBV) between 2020 and 2023, according to data gleaned from the GBV national dashboard.

Agbakaba added that 1,145 of the recorded GBV cases were fatal, 9,636 open cases, 3,432 new cases, 1741 closed cases, 1,895 follow-up cases while 393 perpetrators were convicted within the period.

Former Minister of Women Affairs, Pauline Tallen, also said that 11,053 SGBV cases against women and girls were recorded with 401 fatal cases, 592 closed cases, 3,507 open cases and 33 perpetrators convicted as of November 2022.

A 2022 data by the World Bank on violence against women and girls show that almost one in three women across the world have experienced either intimate partner violence (IPV) or non-partner sexual violence or both. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the two regions with the highest known prevalence of IPV. The data shows that 33 percent of women in the region aged between 15 and 49 have suffered IPV in their lifetime and 20 percent in the last year alone.

Data by the World Health Organisation (WHO) noted that young women between the ages of 15 and 19 are most affected by IPV, adding that by the time they are 19 years old, almost one in four adolescent girls who have been in a relationship have already been physically, sexually or psychologically abused by a partner.

A survey carried out for the purpose of this report on knowledge of non-physical abuse and actions taken found that of the 35 female respondents, 18 (51.4 percent) and 13 (37.1 percent) of who are aged 21 to 35 and 36 to 50 years, respectively, have experienced one form of non-physical abuse or the other. These include emotional trauma and abuse (12 or 36.4 percent), verbal abuse and attack (nine or 27.3 percent) and others like gas-lighting, maltreatments, manipulative words (12 or 36.4 percent).

The survey also found that the respondents, who have either acquired an education to first degree level (18 or 51.4 percent) or above first degree level (18 or 48.6 percent), have experienced non-physical abuses as married (14 or 40.0 percent), single (nine or 25.7 percent), courting and dating (three or 8.6 percent, respectively), single not dating and none (two or 5.7 percent, respectively) and widowed and separated (one or 2.9 percent, respectively).

Though 27 (77.1 percent) as against eight (22.9 percent) of the respondents said women should report cases of abuse if not physical, only two (5.9 percent) have reported a case of non-physical abuse to law enforcement agencies while 32 (94.1 percent) have never reported such cases.

Abuse takes various forms

Though cases of non-physical abuse are often taken for granted, it is the daily reality many women in Nigeria endure. Many rely on religious leaders for guidance, and in some cases are guided by a misconception of religious teaching concerning the position of women. They therefore remain in the abusive relationship.

For instance, despite bearing the burden of feeding and paying the school fees of her children, Zainab (not real name), a petty trader in Niger State, North Central Nigeria, still hopes that her husband will change with prayers.

“Sometimes, I run to my family for help. But my case is even better. In my compound, there is a woman that prefers that her husband beats her because he hardly talks to her. He only brings food home when he feels like it. That is the level of non-physical violence we face on a daily basis.”

“He is my husband and I have to live with him no matter what happens. I keep praying that God touches his heart,” Zainab, who is in her 40s, said in Hausa.

For Laraba (not real name), a mother of four in her 40s, women who are subjected to emotional abuses from their spouses are made to choose between enduring and leaving their marriages, a dilemma that forces them to stay in abusive relationships.

“Despite having a job and sufficient money to support the family, my husband intentionally chooses not to. But he buys things and spends lavishly on himself. When he decides to, the upkeep money he provides barely lasts us a day or two. Yet, he comes home expecting me to have fed the children. Currently, the country’s economy isn’t doing too well and I am unable to find employment to support my family.

“It is not uncommon to see men treat women badly as soon as they enter their homes. For instance, it hurts a lot when my husband ignores and disrespects me despite my best efforts to respect and love him. Perhaps he prefers partners that drag, yell and brawl with him, even hurling insults at his parents,” Laraba said in Hausa.

This pattern of abuse, according to the United Nations, can manifest in any relationship and “is used to gain or maintain power and control over an intimate partner. Abuse is physical, sexual, emotional, economic or psychological actions or threats of actions that influence another person. This includes any behaviours that frighten, intimidate, terrorise, manipulate, hurt, humiliate, blame, injure or wound someone.”

Kemi (not real name) who is in her 30s and a survivor of non-physical abuse, said her husband has denied her sexual intimacy for months and neither provides for the family’s household needs nor their child’s education.

The trader, who is based in Osun State, south west Nigeria, said, “By next April, it will be a year we have made love together. He doesn’t take responsibility as a father or a husband. I am the one doing everything including paying our daughter’s school fees and anything pertaining to the upbringing of the child.

“I have told him many times but he will turn deaf ears to it and I am tired of complaining all the time. I have reported him to his family and they have spoken to him but it is still the same; my husband is very adamant.

“He is a bike man but even the feeding, at times I do it. Even when his bike is faulty, I will be the one running helter and skelter to find somewhere to borrow money. If he refuses to pay back the money, I will be the one to pay it. When it is only one person doing all the responsibility you know how the burden will be.”

“He doesn’t have sex with me, he doesn’t do anything. The only thing I know I married him for is just to cook. He will come back home from work to eat. We don’t even gist, we don’t chat together, we don’t play together. When he is free, he prefers listening to his radio. Since I have noticed that, anytime he returns from work, I will enter my room since we don’t sleep on the same bed and that is how he said he wanted it.”

She said though she had contemplated leaving her home, the thought of how her child will fare in her absence keeps her glued and suicide is not an option.

Abigail (not real name), a middle aged woman, left her marriage after battling severe health challenges. She became acutely hypertensive and was later diagnosed with cardiomegaly, a condition of having an enlarged heart. For most part, she suffered mental illnesses. “Yes I started having mental imbalance; I suffered multiple depressions. I will just be talking. Now, most times I can stay quiet for like two hours and I’m like where is this coming from? It was as bad as that,” she said.

Abigail was advised to undergo surgery for her condition but she took the decision of leaving her marriage instead and her medical issue sorted itself out. She said “Now I don’t sleep on drugs anymore. I don’t remember the last time I took paracetamol.”

Her story was that of multiple abuse; religious, emotional, verbal, economic and other forms of non-physical violence. She said she was chased out of her matrimonial home countless times by her husband and was once chased out with a 41 day old child and had gone several days in the same clothes, squatting around her compound after being chased out by her husband.

As a pastor married to an assistant pastor of a local church, it was difficult for Abigail to seek the right kind of help. She faced intimidation from the leadership of the church and was told to lie about securing a deep cut on the head from an abuse by her husband.

“I remember vividly on the bed my pastor was warning me that I should not discuss this with anybody as I know all eyes would be on me when I get to church on Sunday. In fact, they cooked a story for me to tell people, that I was cooking in the kitchen, NEPA took the light and I hit my head. And that was what I was telling people because so many factors were involved in the religious aspect,” she said.

Badira (not real name) didn’t work for five years after she got married to a man she believed was her friend. After she got a job, she said her husband felt intimidated and would always find ways to make her less visible.

She said, “Even on social media, he would tell me don’t do this, do that, don’t put your pictures on Facebook and all that. I realised that he had this kind of insecurity, thinking I would push higher than what he is doing.”

Students are not left out

It is also worthy to note that non-physical abuses are not only perpetrated in marriage relationships and happen across various social strata.

On our visit to the University of Calabar, Cross River State where the Dean of the Faculty of Law, Professor Cyril Ndifon, was recently suspended by the institution following a protest by female students over alleged sexual harassment and other untoward advances, we found that female students have had to endure non-physical abuses from lecturers and male students alike.

The students, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, said this has taken a toll on their self-esteem, learning and general stay in the institution.

“There was a time I was going to school, I think that was in 2021, I was in a shuttle and I felt something like someone touching my back and I thought it was someone’s bag that was touching me but it was consistent and the next thing, I felt a grab on my ass and I turned and looked at him. He was a law student wearing a uniform. I was scared, I couldn’t even say anything, I couldn’t even tell people around me that someone just touched me or anything. The only thing I could say was insults on him. And I could not enter [a] shuttle for like three months because I was not feeling comfortable till I gained my confidence back,” one of the students said.

Another female student said the exam officer of her former department almost frustrated her for reasons she didn’t know, insisting that she must withdraw from her new department on claims that her results were under probation.

Though it took the intervention of lecturers and professors in her former department for the matter to be resolved, the effect remains life-long. “I even had to almost defer a whole session. I slumped twice in school because of depression at the library. Even my family doesn’t even know about this. When they talk about the school and try to get me upset , I will tell them they don’t know what I have encountered and have faced personally and I can’t even discuss it with them,” she said.

What are the effects of non-physical abuse against women and girls?

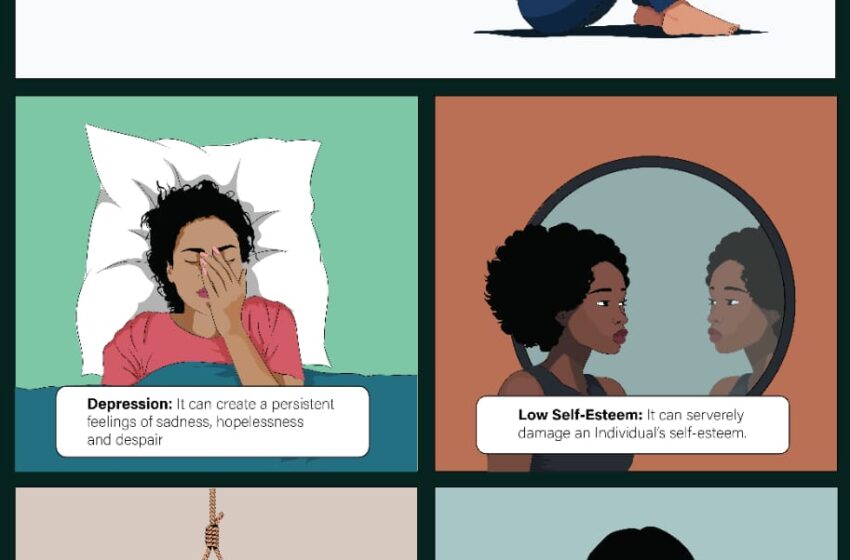

Experts say the effects of the non-physical variant of abuse against women and girls are far-reaching given that there are no physical traces and signs of it. They agree that such abuses are deadlier as survivors struggle with the double jeopardy of breaking free from their abusers and being believed. The World Bank adds that violence against women and girls affect their physical, mental, sexual, reproductive health, a two-to-three-fold increased risk of depression and even suicide.

Dr Ejiro Otive-Igbuzor, a gender expert based in Abuja, said most victims of non-physical abuses go about with smiles to mask the deep-seated hurt they go through.

She said, “Physical violence is bad enough but non-physical violence might even be worse because the person not bearing the pain might not know; you might not notice what is going on in a person’s life. Some people are able to go through that and still wear a smile just to pretend that all is well. And unfortunately, it can be a deadly killer.

“When you go through non-physical violence your blood pressure can shoot up, you are going through mental health issues, people slide into depression. When you see people jump into the lagoon, you don’t know what they have experienced that could lead to that. Many people have taken their lives because of non-physical violence and because it is less obvious so people tend not to address it the way it should be addressed.”

Dr Blessing Ntamu, a psycho-therapist further elucidates on these effects: “Verbal violence is reported less because survivors have a problem of thinking if they will be believed or not.

“A lot of people want to see evidence before they believe you have been abused but with verbal violence, there is no evidence you know but then the scars actually run deeper than that of physical violence. They are always there under the surface, right in the unconscious of the individual’s personality and they are always struggling to come into the consciousness so they create a kind of psychological conflict and so it is even more dangerous than physical violence.”

How does non-physical abuse work?

Dr Jibril Abdulmalik, an Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the Department of Psychiatry, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, noted that victims of non-physical abuses go through such abuses in phases such as shock, denial, helplessness and resignation, internalising their pains, anxiety and disorders like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), heightened anxiety, among others.

He said the targets of perpetrators of non-physical abuses against women and girls are their victim’s sense of self-worth and alienating them from their social support system like friends and family.

Dr Abdulmalik said this pattern of abuse ensures that victims are solely dependent on the perpetrators and constantly seeking validation from them, leading to a vicious cycle of abuse they find difficult to break away from.

“Those who usually perpetrate non-physical violence target your sense of who you are, your self-confidence, your self-esteem and damage it so that you feel very lost and incapable, incompetent, not good enough and that is part of the abuse. So, at the end of the day you become uncertain; you lose your confidence.

“When you have someone who is a perpetrator of gender-based violence, physical or non-physical, what they first do is they break your support structure; cut you away from your friends and family. They alienate you from your social support structures so that once you are isolated, they can be dealing with you and nobody will see it and nobody will stand up for you.”

For Dr Ntamu and Dr Abdulmalik, the first step towards ending the cycle of non-physical abuse is identifying the ‘red flags’ and tell-tale signs of abusers and to always speak out. They also advised survivors to prioritise and look out for their self-worth and for individuals to be each other’s keeper.

“Firstly, work on yourself; build your self-esteem, build your self-confidence, build your sense of self-worth and don’t settle for less. Don’t allow anybody to treat you like trash. Don’t give an inch before they take a mile. Treat yourself as deserving of being treated with dignity, with respect and people will accord you that.

“The second is let’s watch out for one another. You should stay in touch with close friends, with your siblings; check on them, find out what is going on in their lives, don’t assume. Because sometimes, nobody is going to come to you with a red flag before you notice, if you are not close to them, if you don’t visit, if you don’t have long conversations with them regularly, you will not know when something goes amiss,” Dr Abdulmalik said.

Having underscored the prevalence of non-physical abuses against women and girls in Nigeria, what channels are available for survivors to seek remedy? How efficient have Nigerian laws and policies prohibiting violence against persons been in addressing the issue? Why has cases of non-physical abuses persisted in Nigeria despite that the country is a signatory to many international laws prohibiting violence against women and girls including the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) of 1979?

These and other aspects of non-physical abuse against women and girls in Nigeria will be explored in the second part of this report. Read it here.

This report was produced as part of the African Women in Media (AWiM) Reporting Violence Against Women and Girls (VAWG) project.