Should JAMB be removed? Critical look at Nigeria’s education crisis

JAMB’s new cut-off mark: Progress or a path to mediocrity?

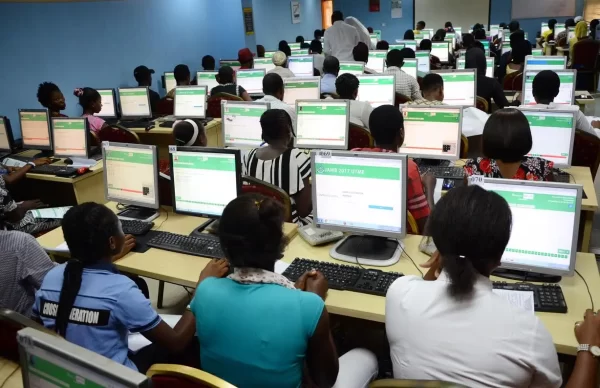

The recent tweet by Mr Peter Obi on X, has reignited a long-standing debate about the state of Nigeria’s education system and the role of the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB) in it. Obi’s post highlights a staggering statistic: of the 1,955,069 candidates who sat for the 2025 JAMB exams, only 420,000 scored above 200, leaving over 1.5 million 78% below this threshold. This alarming failure rate, coupled with Nigeria’s lagging university enrollment paints a grim picture of an education system in crisis. Obi attributes this to decades of underinvestment in education, a sector he argues is the “most critical driver of national development.” But does this mean JAMB, the gatekeeper of college admissions in Nigeria, should be scrapped? This piece is set to explore the figures, the systemic issues, and the relevance of JAMB in today’s Nigeria.

Why JAMB should be removed

The 78% failure rate Obi references is not a mistake but part of a disturbing trend. A 2024 report noted that only 14% of students passed Nigeria’s university entrance exams in 2023, a crisis that has persisted for years. JAMB, established in 1978 to standardize university admissions, has increasingly become a wall rather than a bridge. With over 1.5 million candidates scoring below 200 in 2025, the question arises: is JAMB testing the right competencies, or is it merely exposing the rot in Nigeria’s foundational education system? The latter seems more possible. A score of 200 out of 400 is a modest 50%. However, 78% of candidates could not achieve it. This points to deeper foundational failures in primary and secondary education, where underfunding, corruption, and disparities between the rich and poor have created an uneven playing field.

JAMB’s one-way approach also fails to account for Nigeria’s diversity. Rural students, often attending under-resourced schools, are at a significant disadvantage compared to their urban counterparts. The exam’s high-stakes nature fosters a culture of “special centers” and exam malpractice. Moreover, JAMB’s focus on a single exam ignores alternative pathways to higher education, such as vocational training or direct university assessments, which could better serve Nigeria’s diverse population. Critics highlights the sadness and anxiety many students face, suggesting that scrapping JAMB could open up more equitable admission processes, such as school-based assessments or regional entrance exams tailored to local educational needs.

RELATED STORIES

JAMB: Common reasons students fail, get low marks in UTME

JAMB champions: Meet UTME top scorers in the last 10 years and their success secrets

‘120, 160, 140’ — concerns over JAMB’s cut-off marks for varsities in last six years

Why JAMB must continue despite recent failures

On the other hand, JAMB serves a critical purpose in a country with limited university capacity. Nigeria’s 2 million university students are a fraction of what the population demands. Turkey, with a population of 87.7 million, has over 7 million university students, as Obi notes. Without a centralized system like JAMB, universities would be overwhelmed by applications, potentially increasing corruption in admissions processes. JAMB’s standardized testing, while flawed, provides a little way of fairness in a system where nepotism and bribery dominates. The board also collects valuable data, like the 2025 figures Obi cites, which can inform policy decisions, though this depends on a government willing to act on such data.

JAMB’s role in regulating admissions also ensures that universities maintain some academic standards. Without it, institutions might lower entry requirements to fill the void, further eroding the quality of tertiary education. The real issue, then, may not be JAMB itself but the ecosystem it operates within. If 78% of candidates fail to score 200, the problem lies in the years of education leading up to the exam, not the exam itself. Scrapping JAMB without addressing these root causes like underfunding, shortage of professional teachers, and outdated curriculum, would be similar to treating a symptom while ignoring the disease.

JAMB’s relevance in today’s Nigeria

In 2025, Nigeria faces a youth bulge, with millions of young people eager for education and opportunities. The 78% failure rate in JAMB exams is not just a statistic it represents millions of dreams deferred, a generation at risk of unemployment and poverty. Obi’s comparison to Bangladesh, which has surpassed Nigeria in the Human Development Index despite a smaller population, underscores the urgency of the situation. Education is indeed the “most powerful tool for lifting people out of poverty,” as Obi states, but JAMB, in its current form, is not equipped to deliver on that promise. However, removing it entirely risks chaos in an already strained system. The government must instead focus on holistic education reform, using JAMB as a partner, not a scapegoat.

Conclusion and recommendations

Peter Obi’s tweet lays bare the deep-rooted challenges in Nigeria’s education system, but scrapping JAMB is not the solution. The 78% failure rate is a symptom of decades of neglect, corruption, and underinvestment issues that predate JAMB and will outlast it if not addressed. Rather than abolition, JAMB needs reform to become more inclusive, flexible, and supportive of Nigeria’s diverse student population. A new Nigeria, as Obi envisions, is indeed possible, but it requires a new approach to education one that invests in every level, leverages technology, and ensures that no Nigerian student is left behind. JAMB can be part of that future, but only if it evolves to meet the needs of today’s Nigeria.