When the light went out… examining the controversy over Power Autos’ death

BY Favour Essien Ibanga

The generator died first. Then the music stopped. In the sudden darkness, students at the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies bonfire couldn’t see the jackknives glinting in the hands of strangers who had just crashed their party. They could only hear the shouting, the scattering of DJ equipment, the screams, and the desperate sounds of vendors trying to protect their goods as chaos consumed what should have been an ordinary Friday night celebration.

When the lights came back on, 29-year-old Nweze Chiebonam known as Power Autos, was bleeding. Twenty minutes later, when security finally arrived at the venue they’d been paid to protect, it was already too late.

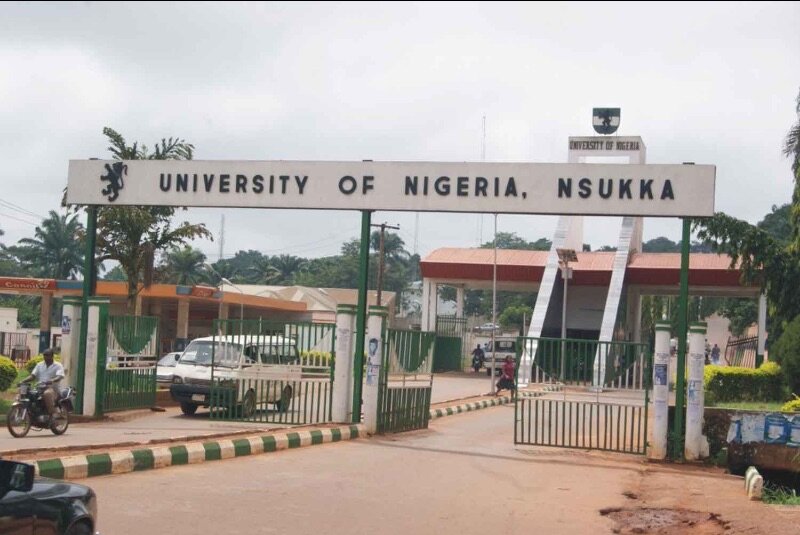

That twenty-minute delay would be the first failure. What came after, a cascade of conflicting statements, internal disputes, and sweeping policy changes, would become equally troubling. By the time the dust settled, the University of Nigeria, Nsukka would have suspended its entire student government, cancelled beloved traditions across campus, and left students to deal with the aftermath of a tragedy that exposed weaknesses at multiple levels of campus leadership.

THE NIGHT EVERYTHING CHANGED

September 12, 2025, started like any other Friday night on UNN’s campus. The Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, in collaboration with the departments of Tourism Studies, Combined Arts, and History and International Studies, had organized a bonfire party. The organizers called for vendors to set up stalls. They hired DJs. They formally wrote to security personnel and paid them to be present. Everything was supposed to be routine.

“I didn’t even organize the event,” the Faculty Director of Socials would later tell this reporter, speaking on condition of anonymity to avoid institutional backlash. “I was just there to support my classmate, whose older brother was Power Autos. It was a departmental thing, nothing to do with the faculty.”

Power Autos whose real name was Nweze Chiebonam dealt in cars, hence the nickname. That night, he drove his own vehicle to the bonfire, parked it near the venue, and settled in to participate in the festivities.

Around 10 p.m., a white Mercedes GLE began reversing in the crowded parking area and collided with Power Autos’ car. What should have been a minor exchange of some heated words, then everyone moves on, turned out as a murder case. This incident exposed the weakness in UNN’s campus safety systems and student leadership structures.

“Power Autos confronted the guys who did it,” the Faculty DOS recalled, his voice still carrying the disbelief of that night. “But these men, we didn’t know them and had never seen them before”

The confront escalated into shoving. Then the strangers reached into their vehicle and emerged with jackknives.

“Before anyone could understand what was happening, they were fighting,” the witness said. “That’s when they went for the generator.”

The venue plunged into darkness. In the confusion, the attackers destroyed the DJ’s equipment, scattering speakers and upending tables. Vendors who had set up shop for the night watched helplessly as their goods were trampled. Students ran in every direction, phone flashlights bobbing in the darkness like fireflies scattering from a disturbance.

After their destruct, he men from the GLE drove away. Friends surrounded Power Autos, urging him to leave immediately. But as he began to leave, the white GLE came back.

This time, there was no argument, no posturing. The attackers went straight for Power Autos. The jackknives that had been used for intimidation moments before now became instruments of murder. In the confusion and darkness, in front of dozens of fleeing students, Power Autos was stabbed.

And the security guards who were supposed to be protecting this event? They were nowhere to be found.

TWENTY MINUTES: THE FAILURE THAT STARTED IT ALL

“These are security we wrote a letter to and also paid to be at the venue,” the Faculty DOS said. “They showed up twenty minutes after it happened. Twenty minutes.”

Let that sink in. Event organizers had followed every protocol. They submitted a formal request letter. They paid the required security fees. Campus security had accepted the assignment, taken the payment, and presumably confirmed they would be present. Yet when violence erupted, when strangers with knives attacked a guest at a university event, security was absent.

Twenty minutes is an eternity in an emergency. In twenty minutes, Power Autos bled out on the ground of a campus department. In twenty minutes, the attackers drove away, leaving the venue before any authority figure arrived. In twenty minutes, students who had paid for protection learned that university security wasn’t there when it mattered most.

By the time security personnel finally arrived, there was nothing to secure. Only chaos, scattered equipment, traumatized students, and a dying man. Friends loaded Power Autos into a vehicle and sped toward UNN Medical Centre. He never made it to the operating room.

A man who had come to support his brother’s campus social event was dead before midnight, killed by strangers over a fender bender, at a supposedly secured university function.

The twenty-minute security failure should have been the story. It should have prompted immediate questions: Why weren’t security personnel present from the start? What’s the protocol for campus events? How will this be prevented in the future?

Instead, what followed was something far more troubling: a masterclass in how poor leadership and defensive posturing can turn a tragedy into a full-blown institutional crisis.

THE SUG’S FIRST MISTAKE: SHOOTING FIRST, WITHOUT ASKING QUESTIONS

On September 13, less than 24 hours after Power Autos’ death, the Student Union Government released an official statement. Rather than focusing on the security failure that had allowed the murder, the SUG statement did something peculiar: it assigned blame for organizing the event.

According to the SUG, the bonfire had been “an unauthorized event” hosted by the Faculty of Arts Director of Socials, called “Wahala of FASA.” The statement clarified that both the deceased and the attackers were non-students (which was true) and claimed that security had intervened during the first altercation before the perpetrators returned for the fatal second attack, which contradicted the eyewitness account that security arrived twenty minutes too late.

There was just one problem with the SUG’s statement: almost none of it was accurate.

The Faculty Director of Socials hadn’t organized the event. The Faculty of Arts Students’ Association (FASA) hadn’t been involved. Anyone who had seen the event flier, which clearly listed the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies as the organizer, along with collaborating departments, would have known this immediately.

The SUG hadn’t bothered to look at the flier. Within hours, this error was corrected by two separate official bodies within the institution.

THE CORRECTION: SETTING THE RECORD STRAIGHT

The Faculty of Arts Student’s Association, (FASA) was the first to respond, and they didn’t mince words. The official memo was emphatic; the kind of statement organizations release when they’re furious about being falsely accused.

“The said event was NOT organized by the Faculty of Arts Students’ Association,” the statement read, the capital letters practically shouting from the page. “It is incorrect and misleading to hang the event on the above association instead of its host, The Director of Socials, Archaeology and Heritage Studies.”

The faculty made clear that the bonfire was a departmental event, organized by the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies. The Faculty of Arts Students’ Association had nothing to do with it. To blame the faculty was to blame the wrong people entirely. “The faculty DOS’s involvement is entirely false, as he had no hand in hosting the event,” it declared.

Similarly, Dr. Benneth Chukwuebuka Udeh, a lecturer in the Department of Foreign Languages and Literary Studies, released his own statement supporting the faculty’s position. He confirmed that the bonfire was departmental, not faculty-sponsored, and condemned the “spread of unfounded reports concerning the incident.”

FASA President Madueke Emmanuel told this reporter what happened behind the scenes. On the UNN Faculty Presidents’ WhatsApp group, where campus leaders coordinate, he posted the original event flier. The graphic clearly showed the Department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies as the organizer, with collaborating departments listed. No mention of FASA. No involvement of the Faculty DOS.

“I showed them the evidence,” Emmanuel explained. “The flier was right there. It clearly said which department organized it. I requested that the SUG release a correction.”

So now, less than 24 hours after a man’s death, the situation was clear: The SUG had rushed out a statement blaming the wrong people. The SUG had gotten the basic facts wrong. A responsible leadership would acknowledge the error, apologize, correct the record, and move on to the actual issue: why security failed.

That’s not what happened.

THE DELETED MEMO: WHEN COVERING UP BECOMES WORSE THAN THE MISTAKE

The SUG did issue a correction. Briefly.

“They put out a counter-memo,” Emmanuel said, “but deleted it soon after.”

Think about what this means. The SUG had been presented with irrefutable evidence, a flier showing they’d blamed the wrong organization. Two official bodies had corrected them publicly. The SUG acknowledged their mistake by issuing a correction. Then, instead of leaving the correction up and allowing the community to move forward with accurate information, they deleted it.

Why delete a correction? Why hide an acknowledgment of error? The decision suggests something troubling about the SUG leadership’s priorities: protecting their image mattered more than ensuring students had accurate information about a campus death.

The deletion had immediate consequences within the SUG itself. According to multiple sources familiar with internal proceedings, the SUG Speaker, seeing the disrupt caused by the false accusations and the deleted correction, attempted to suspend the SUG President.

The constitutional mechanism exists for exactly this kind of leadership failure: when the president’s decisions threaten the integrity of the union, the house can vote for temporary removal while matters are investigated. But the Speaker couldn’t secure the required one-third vote.

The suspension attempt failed, but the damage was done. Internal SUG drama was now public. Blogs picked up the story. Campus tabloids ran headlines about constitutional crises. WhatsApp groups exploded with rumours, some saying the President had been removed, others claiming corruption investigations, a few suggesting the entire executive would be dissolved.

WHEN THE ACCUSED FIGHTS BACK INSTEAD OF FIXING THE PROBLEM

On September 15, three days after Power Autos’ death, the SUG President released a lengthy statement. Titled “Affirming the Legitimate Mandate of the SUG President and Union Members Against Malicious Allegations and Unlawful Indefinite Suspension,” it was part defence, part counterattack.

The President called the suspension attempt “spurious,” and the allegations “malicious fabrications,” and the entire affair an attempt by “political adversaries” to “weaponize falsehood” and “destabilize the Union.” He invoked “the rule of law, the principles of natural justice, and the integrity of our Union.”

What the statement didn’t do was address any of the substantive issues. It didn’t explain why the SUG had falsely blamed FASA. It didn’t justify why the correction was deleted. It didn’t acknowledge that two separate bodies had to correct the SUG’s misinformation. And most critically, it didn’t say anything about the security failure that had cost Power Autos his life.

Instead of accountability, students got defensiveness. Instead of answers about the twenty-minute security delay, they got constitutional arguments about suspension procedures. Instead of leadership demanding that the university fix its security systems, they got a student government more concerned with its own internal drama than with the safety of the students it represented.

The Dean of Students’ Affairs, watching this spiral of accusations and counter-accusations, made a decision. Citing the need to reduce “fake news and misinformation,” the Dean’s office restricted social media publications about SUG matters.

The irony was bitter. The SUG, which had initiated the misinformation by falsely blaming FASA, was now the subject of restrictions meant to combat misinformation. And students throughout UNN spent the remainder of September handling conflicting narratives, trying to understand what had actually happened while their elected representatives fought each other instead of fighting for answers.

“ZYNO TOPBOY CAMPUS TOUR”: THE DECISION THAT ENDED EVERYTHING

If there was any doubt about whether the SUG leadership understood the gravity of what had happened, that doubt evaporated on September 20.

Eight days after Power Autos bled to death at a bonfire party, the Student Union Government announced another bonfire party.

The event was titled “Zyno Topboy Campus Tour.” This time, the SUG said, it would be held off-campus at Nsukka Stadium. The announcement landed like a grenade in WhatsApp groups still processing the previous week’s tragedy.

Some students saw it as tone-deaf. Others viewed it as defiant. A few wondered if the SUG had completely lost touch with reality. Here was a student government that had falsely accused an organization of hosting the deadly bonfire, deleted their correction when caught, survived a suspension attempt, and was now under restrictions from the Dean’s office for spreading misinformation. Their response? Organize the same type of event that had just gotten someone killed.

The timing couldn’t have been worse. Power Autos’ family was planning his funeral. The investigation into his death was ongoing. Students were still traumatized. Campus was tense. And the SUG thought this was the appropriate moment for “Zyno Topboy Campus Tour.”

For university administrators who had been watching the SUG’s cascade of poor decisions, this was the final straw that made them react swiftly.

WHEN THE UNIVERSITY SAYS IT’S ENOUGH

On Friday, September 26, the UNN management held an emergency meeting and announced the immediate and indefinite suspension of all SUG activities.

According to the Registrar, Dr. Mrs. C.N. Nnebedum, the move was necessary following “media publications and counter-publications concerning the Union’s affairs” that contained “serious allegations with the potential to disrupt peace and order on campus.”

That same day, Vanguard Newspaper reported that two suspects, Ezema Onyedikachi (27) and Ugwu Chigozie Anthony (21), were arraigned and charged with murder and conspiracy. Police spokesperson Daniel Ndukwe confirmed that they had been remanded in correctional custody.

The SUG had essentially self-destructed. Through a combination of false accusations, deleted corrections, internal power struggles, defensive posturing, and catastrophically poor judgment about organizing another bonfire, they had given the administration every justification needed to shut them down completely.

So, on September 26, accountability moved forward on one front: the criminal justice system was prosecuting the men who wielded the knives. But the security personnel who took twenty minutes to respond to an emergency? Not mentioned. The administrators overseeing campus security protocols? Not addressed. The system that allowed non-students to bring weapons to a university event? Not reformed.

Instead, the university suspended the student government and turned its attention to the easier target: restricting student activities.

WHEN COLLECTIVE PUNISHMENT REPLACES ACCOUNTABILITY

The new administrative policies extended far beyond the SUG.

The university banned the traditional final-year sign-out celebrations, calling them “wild celebrations” that disturbed campus peace. Students were instructed to hold it only at the stadium a location at the extreme the school.

“There’s no valid reason for stopping the celebration,” said Miracle Ogbonna, a final-year Mechanical Engineering student. “It’s a tradition, and most students are done with exams by then.”

Another blanket policy mandated that all social activities must conclude by 6 p.m. The Department of English and Literary Studies felt the impact immediately. Prof. Chuka F. Ononye, the Head of Department, received instructions that the departmental dinner night could not be held outside the school and could not exceed 9 p.m. Faced with those restrictions, the departmental DOS made the only practical decision and cancel it entirely.

For final-year students in the department, the losses accumulated. The Literary Art Festival, a journal unveiling event unique to the department, where students presented creative work they’d laboured over for months, was cancelled. Cultural Day, where different ethnicities showcased their heritage through food, dress, and performance, was scrapped. Now dinner night, the final gathering before graduation, was gone.

“The literary art festival, cultural day, and now dinner night is all cancelled. What’s the need of buying six-yard Ankara?” lamented Favour Asadu, a final-year English and Literary Studies student.

These weren’t the students who organized the bonfire. These weren’t the departments whose security failed. These weren’t the SUG leaders who spread misinformation or tried to organize another bonfire too soon. These were only students across campus whose only connection to September 12 was that they attended the same university.

But they were the ones being punished.

THE QUESTIONS THAT STILL MATTER

In the week that followed some fundamental questions remain unanswered:

Why did the security delay to respond? Event organizers followed protocol. They submitted paperwork. They paid fees. Security accepted the assignment. Yet when violence erupted, security wasn’t present. Were they understaffed? Were they at another location? Was there a communication breakdown? Has anyone been disciplined? Has the security contract been reviewed? The university hasn’t said.

What’s the protocol for campus emergencies? If violence breaks out at a university event, what’s supposed to happen? Who do students call? What’s the expected response time? Are there panic buttons? Emergency numbers? Designated safe zones? Students deserve to know what systems exist to protect them. The university hasn’t explained.

Will the new policies prevent another tragedy? The restrictions focus intensely on when students can gather (not after 6 p.m.) and what they can do (no “wild celebrations”). But none of the new policies address security response time. None require additional security personnel at events. None establish clearer emergency protocols. The policies restrict student activity without reforming the institutional failure that allowed the murder.

Why is restricting students easier than fixing security? The administration moved swiftly to ban student celebrations, impose 6 p.m. curfews on social activities, and suspend the SUG entirely. Those decisions came within weeks. Meanwhile, there’s been no public announcement about security reforms, no new emergency protocols, no accountability for the twenty-minute delay. The message is clear: changing student behaviour is simpler than fixing institutional failures.

How can students and blogger be sensitized on spreading fake news and misinformation? Part of the upheaval arose from the different news that flew around from blogs to tabloids to different official memos. What can be done to instil ethical reporting to the blogs? Was suspending them from writing on the issue enough?

WHAT THIS REVEALS: WHEN LEADERSHIP FAILS, TWICE

The bonfire tragedy exposed two separate but related failures of leadership at UNN.

The first failure was operational: Security that was paid to protect students didn’t show up when violence erupted. Twenty minutes passed before help arrived—twenty minutes in which a man bled to death and his killers escaped. This failure belongs to whoever manages campus security, whoever approved the security arrangements, whoever was supposed to ensure that paid personnel actually do their jobs.

The second failure was leadership: Instead of immediately demanding answers about the security breakdown, the Student Union Government rushed to assign blame for organizing the event and got it wrong. When corrected by official sources with documentary evidence, they briefly acknowledged their error then deleted the correction. When the campus was still reeling from tragedy, they announced another bonfire party.

The SUG’s maze of poor decisions gave the administration cover to shut down student governance and implement sweeping restrictions without addressing the actual security problems. Students lost their elected representatives and their traditions, while the security system that failed Power Autos remains

What students have instead is a campus where their final-year celebrations are banned, their social activities restricted, their student government suspended, and their trust in institutional leadership, at both the student and administrative level was shattered.

THE AFTERMATH

As this article goes to press, Power Autos’ family mourn their son, brother, and friend who went to support his younger sibling and never came home. The two men accused of killing him sit in correctional custody awaiting trial. Security personnel who took twenty minutes to respond continue their duties, unremarked upon by official statements. The SUG leaders whose misinformation and poor judgment led to their own suspension have gone silent, their promised “integrity” and commitment to “dignity” nowhere evident in the aftermath of their failures.

And students at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, Nigeria’s self-proclaimed “Premier University”, are left with cancelled celebrations, unused Ankara fabric, and a sobering lesson about institutional priorities.

When tragedy strikes, their leaders’ first instinct wasn’t to demand accountability for security failures. It was to assign blame, incorrectly. When corrected, the instinct wasn’t to accept responsibility. It was to delete the correction. When campus needed thoughtful leadership, the instinct was to organize another bonfire party.

And when institutional failure cost a life, the solution wasn’t to reform security systems. It was to restrict students.

The new policies tell students when they can’t celebrate, where they can’t gather, and what traditions they can’t continue. What the policies don’t tell students is how the university will keep them safe when the next emergency happens.

Because until someone answers why security failed, why protocols failed, and how the system will be reformed, all the restrictions in the world can’t restore what was lost on September 12.

Not just Power Autos’ life.

But students’ faith that when crisis comes, their leaders (at any level) will prioritize their safety over damage control.

The generator came back on eventually, that night in September. But the trust? That stayed dark.