The 9th NASS, Passive Constitution and Masses Poverty

By Jerome-Mario Utomi

It is globally recognized that every citizen of a modern nation is a subject of the state, and once a state is formed, the citizens formulate ethical principles or virtues to be pursued, vices to be avoided and values to be cherished-for the good conduct of the citizens. These values are in most cases put in, or in some cases left in an uncodified form and transmitted from one generation to the next via a well formulated/structured process called constitution.

This thought may have informed our forebears like their counterparts abroad, to come up at different times and places with constitutions to promote and ensure: a free and democratic society; a just and egalitarian society; a united strong and self-reliant nation; a great and dynamic economy; and a land of bright and full opportunities for all citizens.

Indeed, analysts believe that the constitutions are the foundation for government in virtually every society around the world that simultaneously create, empower, and limit the institutions that govern the society. In doing so, they are intimately linked to the provision of public goods. Outcomes, like democracy, economic performance and human rights protection, are all associated with the contents of countries’ constitutions.

But, beyond these qualities, there’s something more.

There are people in Nigeria who accept as true that the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended) is not the way constitution supposed to work.

Whilemany in this group are of the views that most of its provisions falls short of establishing or clarifying processes for citizen participation in the development and management of their nation’s affairs, to some, the constitution failed to prescribe or specify accountability mechanisms for non-performance or policy infractions, while the rest believes that the major failure of the 1999 constitution is underlined in its inability to focus on highest national priorities.

As an instance, the Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA)-a Lagos Based non-governmental group believes that the nation’s constitution is largely responsible for poor economic and political outcomes in the country.

Their concern comes in double folds.

The first concern is hinged on the fact that history of federal Character enshrined in the constitution is an account of putting square pegs in round holes. In their quest to get appointments equitably spread, states nominate individuals without qualifications, experience or target but on the basics of political patronage. This entrenched anomaly takes toll in our national development aspiration. It is also the reason why the country has not made much progress.

Similarly, while noting that the most serious, most surprising and most fundamental failure of the 1999 constitution is signposted in its inability to carter for the masses social and economic rights, the group lamented that like an unchained torrent of water submerges whole country sides and devastates crops, even so, has the provisions of Chapter 2 of the 1999 constitutions of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended) consequently placed on poor Nigerians more burden than goodwill.

Admittedly, the controversial chapter made some ‘fundamental’ provisions on the duties of the state and its relationship with the citizens. It is titled “Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principle of State Policy”. Section 14(a) provides that “Sovereignty belongs to the people of Nigeria from whom government through the Constitution derives all its power and authority” Section 16 provides the economic objectives of the state to include: Harness the resources of the nation (state) and promote national prosperity and an efficient and self-reliant economy, and; Direct its policy towards ensuring: (i) the promotion of a planned and balanced economic development; (ii) that the material resources of the state are harnessed and distributed as best as possible to serve the common good; (iii) That suitable and adequate shelter, food, water etc. are provided for all citizens.

Despite these fine provisions which conventionally ought to be an end in itself and the crucial enabler to the attainment of other fundamental Human Rights contained in Chapter 4 of the same constitution, the constitution for yet to be identified reasons prescribed the provisions as not justiceable but merely acts as an obligatory guide to what the state should promote and attain.

Not only has the clause remained a paradox of our national existence but what is in some ways more ‘brazen’ is that it designed and laid the groundwork for the atrocities that the nation currently witnesses- corruption, public leadership with neither goals nor target, lack of accountability and transparency in public leadership sphere and provides answers to why poor Nigerian masses have suffered sets of challenges which include but not limited to; deprivations of their Economic, social, and cultural rights including: right to work; the right to an adequate standard of living, including; food, clothing, and housing, the right to physical and mental health, the right to social security, the right to a healthy environment, and the right to education.

Today, public officials neither pay attention to the enhancement of living standards/health of the people nor willing to provide appropriate signals to the private sector to enhance corporate social responsibility or other social intervention programmes to add value to the lives of the ordinary Nigerian. Or feel bound to seriously observe basic standards of care and always unwilling to accept responsibility for their failure to deliver expected quality services.

This is happening in the face of the Revised National Policy on Health (2004), among recent ones which stipulates that“health and access to quality and affordable healthcare is a human right”. And also provides that “a high level of efficiency and accountability shall be maintained in the development and management of the national health system.This is in addition to its declaration that “the people of this nation have the right to participate individually and collectively in the planning and implementation of their healthcare.

The same non-justiciability statutes of Chapter 2 also plagues and accounts for recurrent mismanagement in the nation’s education sector which daily manifests in government’s non-compliance with the United Nation Educational Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s [UNESCO] budgetary recommendation, and other acts opposed to demands of modern affordable and accessible quality education.

What is most troubling is that while chapter two handles issues such as access to education, housing, health and so on which the Constitution describes as non-justiciable and comes under fundamental objectives and directive principle of the state. Chapter four on its part handles provisions that include but not limited to the rights and freedoms of association, expression, right to life, movements just to mention but a few. Secondly, while one can not deprive or deny any citizen of any of the above-mentioned rights in chapter four without committing offence against the individual/ the state, such is not the case of the provisions in chapter two.

The issue for determination arising from the above is that; considering the fact that fundamental human right procedure rule 1999, provided that once there is a perceived threat to life, one has the right to access or proceed to court to seek protection for the violation of such right to life, Keeping this provision in perspective, when one as a result of the failures of state parties is denied access to food or good environment, can’t the citizen make demand as such denial directly or indirectly impacts on his/her life?

Take another scenario, if a citizen, based on the provisions of the said chapter is deprived access to quality education, where and how will the citizen gain the knowledge to recognizing and eventually claim the said fundamental human rights to free speech as enshrined in chapter four?

Even if an answer is provided to the above, it will not in any appreciable way erase the time honoured laws which states that no nation can use its domestic laws to override international obligations? Or have we as a nation forgotten that the Social and Economic Rights are special forms of human rights globally recognized and should be applied with or without domestication?

This fact particularly comes to mind when one remembers that the nation Nigeria’s voluntarily assumed obligations to respect, promote, protect and fulfill the right to health, education among others, under major regional and international human rights instruments, including the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

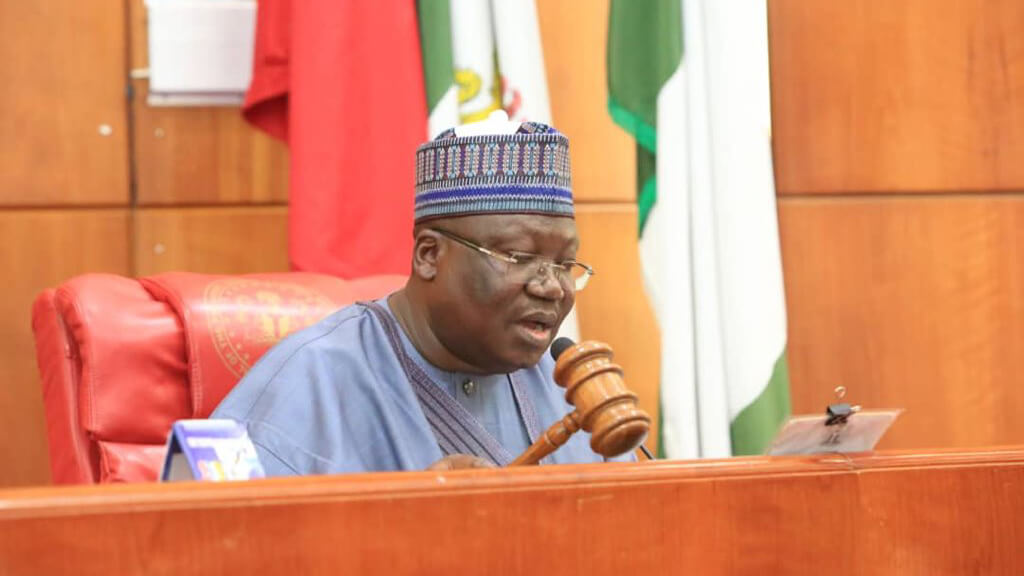

In the face of all these, ‘the question before us could be of no greater moment: will we fail future generations by leaving them a constitution far diminished from what we inherited from our forebears’? Though the 9th NASS were not the people that designed and placed the faulty policy on ground, however, they are in the best position to provide answers to this question.

Jerome-Mario Utomi is with the Social and Economic Justice Advocacy (SEJA)-a Lagos Based Non-Governmental Organization.