How did DNA connect Abraham Ramirez to Arizona assaults?

dna Abraham Ramirez

A sexual assault kit collected more than three decades ago in California has led investigators to a major breakthrough, linking a 55-year-old man to a series of unsolved attacks in Arizona.

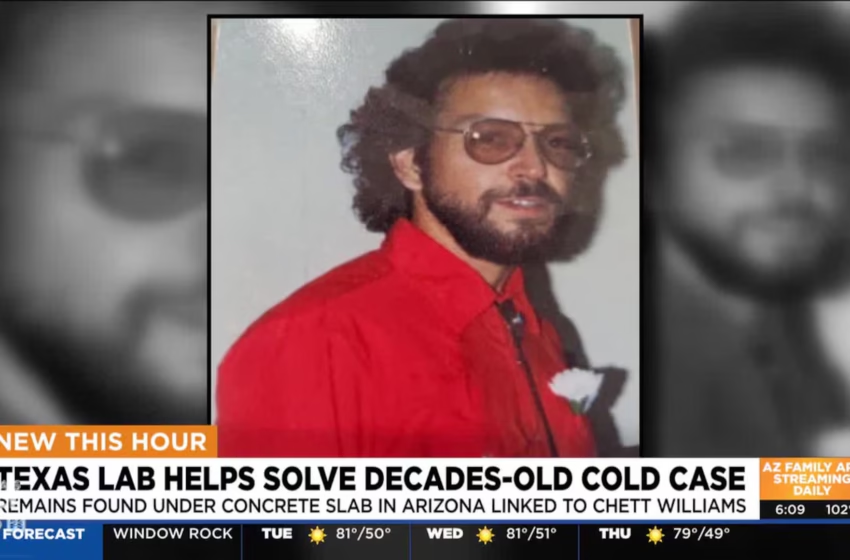

Authorities in Ventura County announced that Abraham Ramirez, previously identified but never convicted in a 1994 sexual assault case, has now been tied by DNA evidence to four separate assaults in Phoenix that occurred between 1998 and 2013.

A Case Reopened Through DNA Technology

The California case dates back to 1994, when a woman managed to escape after being sexually assaulted. Ramirez was named as a suspect at the time, but prosecutors were unable to move forward due to a lack of sufficient evidence. The victim’s sexual assault kit was collected and preserved, though it would remain untested for years.

That changed when the kit was recently analyzed, and Ramirez’s DNA profile was uploaded to the national Combined DNA Index System (CODIS). The results stunned investigators, revealing a direct match to DNA collected in four Phoenix assaults that had long gone unsolved.

Officials Hail Persistence and Technology

Ventura County Sheriff Jim Fryhoff emphasized the importance of testing every preserved sexual assault kit. “No matter how much time has passed, we will use every tool available to pursue justice and stand with survivors,” he said. “This case is a powerful reminder of why our commitment to testing is unwavering.”

Ventura County District Attorney Erik Nasarenko echoed that sentiment, noting how modern forensic science gave survivors a long-delayed path to justice. “Even decades later, testing these kits can uncover the truth and give survivors their voices back,” he said.

Indictment in Arizona

A Maricopa County grand jury indicted Ramirez in August on 11 counts of sexual assault and kidnapping tied to the Phoenix cases. He is currently facing prosecution, though court records indicate no attorney information was available for him at the time of the announcement.

Authorities in both California and Arizona stressed that the outcome underscores the transformative role of DNA testing in solving violent crimes that might otherwise remain buried in cold case files.

Background

When officials in Ventura County, California, announced this week that DNA evidence from a 1994 sexual assault had linked 55-year-old Abraham Ramirez to four cold cases in Arizona, it was hailed as a triumph of persistence and science. But beneath the headlines lies a much longer history — one that exposes how thousands of survivors across the United States have waited years, even decades, for justice.

The 1994 Case That Went Cold

In 1994, a woman in Ventura County reported being sexually assaulted but managed to escape her attacker. Investigators identified Ramirez as a suspect but lacked sufficient evidence to secure a conviction. A sexual assault kit was collected, yet the case stalled and was eventually dismissed. Like so many others at the time, the kit was stored away — preserved, but untested.

At the time, law enforcement lacked today’s advanced DNA tools, and testing was often expensive, time-consuming, or deprioritized. In many jurisdictions, backlogs grew as thousands of kits accumulated in police evidence rooms and hospital storage facilities. Survivors, meanwhile, were left with unanswered questions and little hope.

The Rise of CODIS and the Power of DNA

The breakthrough in Ramirez’s case was made possible by the Combined DNA Index System (CODIS), a national database developed in the 1990s by the FBI. CODIS allows local, state, and federal agencies to upload DNA profiles and search for matches across cases.

Over the years, CODIS has become a cornerstone in solving crimes that once seemed unsolvable. The system has helped identify serial offenders, exonerate the wrongly accused, and provide closure to families. In Ramirez’s case, his DNA — once processed — matched evidence from four sexual assaults in Phoenix between 1998 and 2013.

A National Backlog of Untested Kits

The Ramirez case also underscores a persistent problem: the backlog of untested sexual assault kits in the U.S. By some estimates, hundreds of thousands of kits remained untested nationwide well into the 2010s.

Advocacy groups like the Joyful Heart Foundation launched campaigns such as End the Backlog, pressuring states to commit resources to process every kit. Federal funding initiatives also provided support, but progress has been uneven. While some jurisdictions cleared their backlogs, others struggled with funding shortages, bureaucratic hurdles, or competing priorities.

Ventura County Sheriff Jim Fryhoff emphasized that Ramirez’s case proves why no kit should ever go untested. “No matter how much time has passed, we will use every tool available to pursue justice,” he said.

Survivors and Delayed Justice

For survivors, the delay in testing often meant decades of silence. Many lived with trauma while their cases sat idle in evidence rooms. The Ramirez development shows the cost of inaction — had the kit been tested sooner, investigators might have linked him to the Arizona assaults years before.

Ventura County District Attorney Erik Nasarenko called the outcome a testament to forensic science but also a reminder of what’s at stake: “Even decades later, testing these kits can uncover the truth and give survivors their voices back.”

A Turning Point in Cold Case Justice

Ramirez now faces 11 counts of sexual assault and kidnapping in Maricopa County, Arizona. His indictment comes nearly 30 years after the first kit was collected in California.

For advocates, his case is not just about one man but about a system learning to reckon with its failures. The historical backlog of untested kits has been described as one of the most significant criminal justice issues of the last half-century — a failure that denied survivors both justice and healing.

As forensic science continues to advance, the Ramirez case stands as both a victory and a cautionary tale: proof of the power of DNA, but also a reminder of how long-delayed justice comes at a human cost.