Fighting to Learn: The Integration Struggles of Students with Intellectual Disabilities in Nigeria..

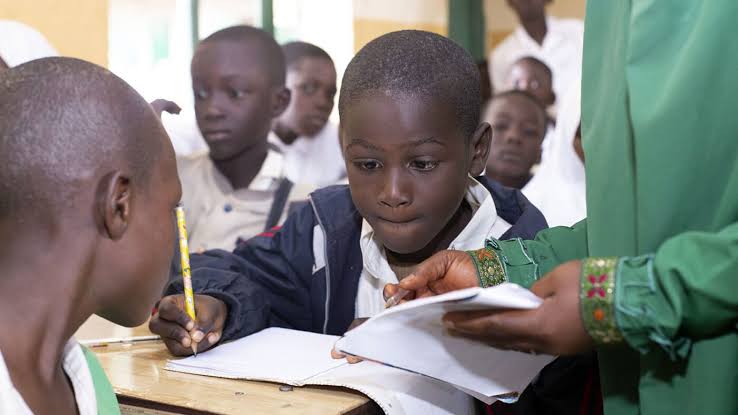

Image Credit: Kabintiok Solomon/ Sight savers Image Source: Inclusive education initiative

By Dorcas Motunrayo Taiwo

Tobiloba Ajayi, a lawyer and founder of Let Cerebral Palsy Kids Learn, was diagnosed with cerebral palsy at birth, a disability that affects 1.5 to 3 children per 1,000 live births but doesn’t receive enough attention.

In an interview, Ajayi revealed the struggles that parents of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities face in trying to ensure their children receive an education.

She said, “When my impact story in the Mandela Washington Fellowship went viral, many parents flooded my social media inboxes. They all had the same question: ‘How did you go to school?'”

She continued, “I didn’t understand what that question meant until a parent broke it down for me by saying, ‘All the schools around me are rejecting my child, and seeing you with all these degrees, I’m beginning to wonder how your parents made that happen.'”

This question reflects the reality for countless children with intellectual disabilities across Nigeria, who face systemic barriers, limited resources, and societal stigma as they strive to receive an education that meets their needs.

Ridwan, an award-winning writer with dysgraphia, had his fair share of struggles. In his words, “When having conversations relating to my learning difficulty, I get emotional. What makes me emotional about the issue is that this particular impairment is not well known; it’s not often spoken about.

“In the society where we live, especially in a setting like Nigeria, the number of people who have knowledge of this learning difficulty is far too small, and that increases the danger. Even teachers, who are supposed to detect these things, don’t know about it either. I’ve seen a teacher who kept hitting her only child because the little boy found it very hard to do certain things.”

Speaking further on his experience, he shared, “I can’t recall the number of times I was bullied in primary and secondary school. I was made to feel like a freak and that I couldn’t do anything. I had to force myself to do things. It wasn’t a physical pain; it was mental. It’s connected to one’s brain, and it can’t even be figured out.

“In my first year at university, I was unable to write. What worsened the situation was that, because I studied English and our department was considered to be for writers, CBT or other computer-enabled examinations or tests were canceled. Since we were literary students, we had to write.

“For all my years at the university, if I had a question paper with five questions to answer, I never managed to attempt more than three. I know for sure that I answered those three very well; I did well. If I had been able to work around the disorder and answer four or five questions, I would have done even better. I never had that luxury because writing was painful for me. I continued to manage my situation and ensured I graduated with a 2.1” Ridwan added.

SEE VIDEO

A health survey shows that about 7 percent of household members above the age of five (and 9 percent of those 60 or older) have some level of difficulty in at least one functional domain—seeing, hearing, communication, cognition, walking, or self-care. Additionally, 1 percent either have a lot of difficulty or cannot function at all in at least one domain.

Also, World Health Organisation (WHO) data reveals that over 35.1 million Nigerians are persons with disabilities, with most being children. However, most PWDs lack access to quality education, which is the painful reality in Nigeria.

Just like the concerned parent who approached Tobiloba Ajayi, many parents of children with disabilities, especially those with intellectual and developmental disabilities, find it difficult to get their kids integrated into society, particularly in terms of education.

Atinuke Odukoya, a parent of 29-year-old Jubelo Odukoya, who has dyslexia and hearing disabilities, shared how her child was not diagnosed early, and how she had to grapple with the failure of the healthcare system after her child’s birth. She highlighted that even the information available on intellectual disabilities is not accessible to every parent and caregiver.

READ ALSO

Learning at a cost: How Nigeria’s education system frustrates PWDs in tertiary institutions

‘Blatant violation of rights’ — Female baker to sue GTB for ‘unlawful account restriction’

Lagos gov’s aide, SPARK Africa CEO, Harvard alumnus… meet YANGG’s AFC2024 speakers

“If the child does not show the physical signs of intellectual disability, like cerebral palsy or Down syndrome, it is more challenging. People do not understand how to deal with that. So, either parents pray for a miracle, or they meet someone who truly understands. Some children are labeled slow learners, but the disability goes deeper than that.

“Thank God, today, there are opportunities in schools using Montessori methods and other approaches that can help with learning. Now, those who are well-off simply take their children out of the country, knowing that they can get the required help.

“For regional exams like the West African Examination Council (WAEC), nobody caters to children with learning disabilities because they don’t know how to. A child with dyslexia writing WAEC is given the same time as everybody else. This child is not stupid or daft; they just require extra time in the exam hall.

“In fact, in some other places, I’ve observed that children with learning disabilities write exams with a carer or someone in the exam hall to support them. Yet, you see children writing WAEC six, seven, eight, or nine times, and everyone is saying they are dull, not brilliant, or not bright. But no, they probably just learn differently.

Atinuke highlights how traditional schooling methods are not suitable for all children, particularly those who are hands-on learners or have disabilities. Physical disabilities also present significant challenges, especially when facilities are not accessible.

She recounted her daughter’s struggle with self-esteem, attending multiple schools without adequate support, and feeling inadequate in an environment focused solely on academic achievements like math and English. She emphasizes the lack of awareness, resources, and financial means for accessing effective support, especially for children in rural areas.”

Image Source: Global sisters report

Ridwan also shared the struggles and negativity these children face. “All the children will think about when a teacher or parent beats them is, ‘My mom hates me, my dad hates me, my teacher hates me.’ When you continue feeding your child such thoughts, you are planting seeds of negativity that will hinder their development and usefulness.

“My mother and father were illiterates, and out of all my siblings, I’m the only one who had the privilege of tertiary education despite all my challenges. None of them knew anything, so without the support of my friends, I wouldn’t have been able to overcome my challenges.”

Meanwhile, Tobiloba Ajayi’s encounter with those parents was the first time she got to hear about overt exclusion and that fuelled are drive to proffer a solution. She said, “That a school would turn back at the door and say stuff like, ‘we don’t take children like this here’, was a first for me.”

She continued, “One in every 100 children born in Nigeria is diagnosed with cerebral palsy—that’s about 50,000 diagnoses in a year. My question is, what is our plan? Because if we’re diagnosing 50,000 people in a year, in 10 years that will be about half a million. If we are not providing half a million people with education, and there is no social structure, somebody has to make a difference. Somebody has to change this narrative.”

The way forward

Awareness is an important tool in ensuring that persons with disabilities (PWDs) with intellectual and developmental disabilities get access to quality education.

Parents, medical professionals, teachers, and all members of society should be sensitised about these kinds of disabilities and how to handle them. If awareness is raised to a large extent, issues of stigma and bullying, like what Ridwan experienced, will be drastically reduced.

Additionally, inclusive education policies should be created to cater to the needs of PWDs with intellectual and developmental disabilities, and existing policies should be enforced.

Lastly, the government should champion inclusion in schools by training educators. Educators need training to understand IDD and effective teaching methods. This includes learning about differentiated instruction, assistive technology, and behavioral support strategies.