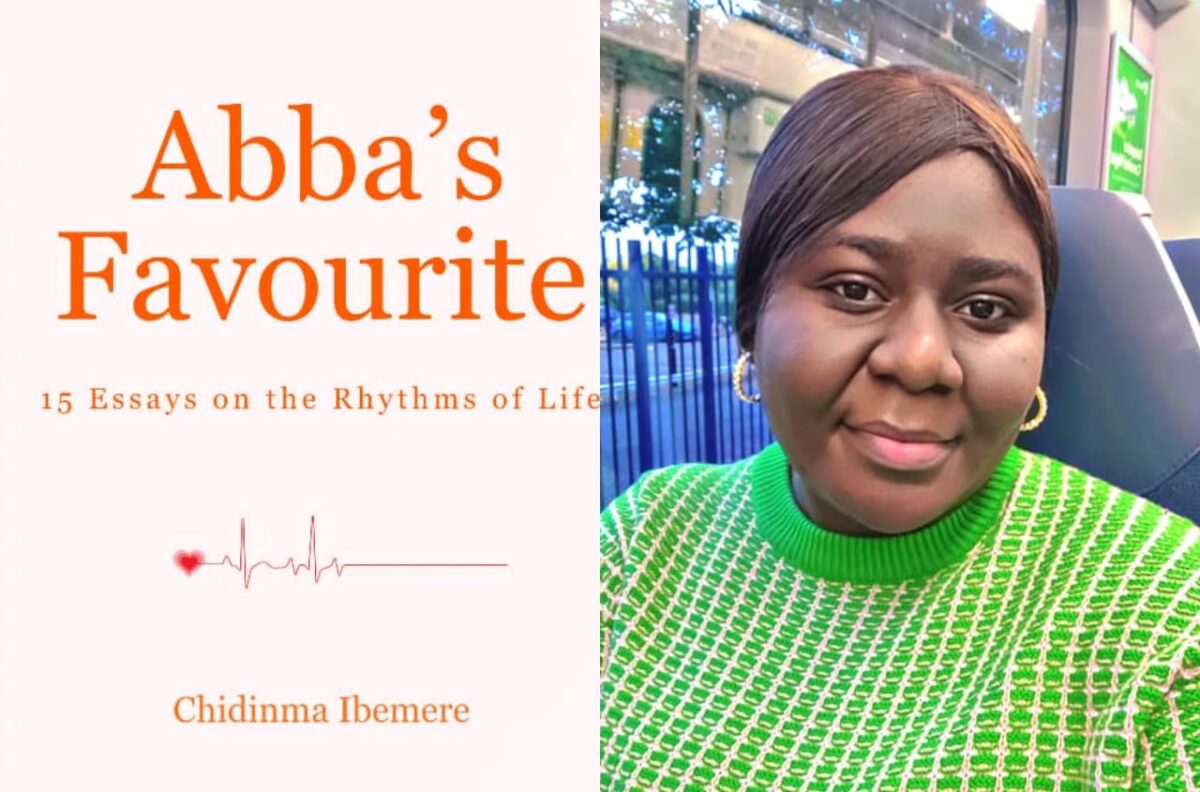

Death’s curriculum: A review of Chidinma’s Ibemere’s writing

By Elizabeth Ayodele

Chidinma Ibemere’s “The Void Caused by Grief” achieves what most grief literature fails to accomplish—it refuses consolation while offering genuine comfort. This is not a grief memoir as therapeutic exercise or self-help manual disguised as narrative. Instead, Ibemere constructs an epistemology of loss, charting how death teaches lessons no living instructor could provide.

The essay opens with radical honesty: “As a young child, I never fully understood grief.” This admission establishes Ibemere’s authority paradoxically through acknowledged ignorance. She positions herself not as a grief expert but as a perpetual student, someone still learning sixteen years after her cousin’s death. This ongoing education—grief as continuous present rather than completed past—distinguishes her work from narratives promising stages, closure, and healing’s finite endpoint.

Her grandmother’s death at age five provides the essay’s foundational vocabulary. Ibemere catalogs absence with devastating precision: empty chair, silenced voice calling “Ugochi,” the well where no one now cautions about dragged feet or mishandled bailers. These sensory details reveal grief’s phenomenology—how loss manifests not as a singular event but as accumulated subtractions, each small absence revealing the magnitude of what’s gone. The grandmother doesn’t simply die; she leaves behind furniture that mocks with its permanence, familiar sounds replaced by “unfamiliar silence,” domestic rituals impossible to perform.

Crucially, five-year-old Ibemere doesn’t remember crying. This admission accomplishes two critical tasks: it validates that grief can exist without tears, and it demonstrates memory’s selectivity in trauma. What remains isn’t emotional display but cognitive conclusion: “I would never see her again.” The child’s mind grasps permanence before the heart knows how to mourn it, intellectual understanding preceding emotional integration.

The illusion of death as age-dependent receives brutal correction with the same-aged girl’s death. Ibemere records her unspoken questions—”How did she die?” “Why did she die?” “Isn’t death for older people?”—with the rhythm of panic. The repetition mimics racing thoughts, mind circling questions “too scared to ask anyone.” This moment indicates adults’ conspiracy of silence around mortality, pedagogical failure that leaves children constructing private terrifying theologies about death’s operation.

Yet Ibemere’s most significant contribution emerges in her treatment of her cousin’s 2009 death. The temporal specificity functions as a memorial act: Saturday, April 4, entrance exam. Wednesday, April 8, final phone conversation about Easter plans. Thursday, unreachable phone. Friday, the news. This chronological precision serves multiple purposes. It demonstrates how ordinary time transforms into a sacred calendar, each date carrying permanent weight. It shows how mundane exchanges become involuntarily precious when rendered final. It captures trauma’s need for exact accounting, as if precise documentation might reveal where intervention could have occurred.

The sensory details achieve devastating effect: running toward the gate upon hearing news, aunt pursuing, the irritation at comforters’ presence. Ibemere’s rage at consolation language deserves particular attention. When she demands, “What exactly was I supposed to do with the words, ‘God knows best’?” she articulates what bereaved people often feel but fear expressing—those theological platitudes offered as comfort compound pain. The phrase “take heart” or “stay strong” functions as dismissal disguised as support, commanding emotional performance when capacity for performance has collapsed.

Her description of grief’s private rituals—crying daily until burial, rereading messages, replaying final conversation—maps the territory of acute mourning with anthropological precision. These behaviors receive no pathologizing label; Ibemere presents them simply as “how I processed it all.” Meanwhile, another cousin “could not even cry,” demonstrating that grief refuses singular expression. This observational generosity—allowing both tears and tearlessness as legitimate—models the anti-prescriptive stance the essay explicitly advocates.

The essay’s most profound insight arrives in its refusal of closure. Sixteen years later, “the void is still there.” Annual birthday remembrances continue. Imagined alternative futures persist—”if he’d be married by now, or if he would have become a tech bro.” The continued present tense—”I still miss my guy!”—suggests that integration, not resolution, characterizes sustainable bereavement. The void doesn’t fill; one builds life around it, accommodating permanent absence without pretending it’s temporary.

Ibemere’s claim that “grief is a process, and a mystery only time can help unravel” acknowledges limits while refusing nihilism. Time doesn’t heal; it reveals, teaching gradually what acute pain obscures. This is grief’s pedagogy—the curriculum no one chooses but everyone eventually studies, learning outcomes unclear until years after enrollment.

The essay concludes with a direct address to grieving readers: “I want you to know that you are not alone.” This moves from testimony to solidarity, personal to communal, transforms private mourning into shared experience. Ibemere doesn’t claim to understand another’s specific loss—that would be false intimacy. Instead, she offers companionship in bewilderment, fellow travelers rather than arriving experts.

What distinguishes this essay in contemporary grief literature is its resistance to instrumentalizing loss. Ibemere doesn’t extract meaning, discover blessing, or perform gratitude for lessons learned. The cousin’s death remains a tragedy, full stop. No redemptive arc softens its edges. The only “value” extracted is knowledge that grief has no template, that supporting mourners requires “empathy” practiced with “genuine care,” and that sixteen years later, love persists alongside absence.

This refusal of a redemptive narrative constitutes a radical act in culture demanding positivity from pain. Ibemere allows loss to remain loss, void to remain void, while simultaneously testifying that life continues, carrying its permanent wounds. The essay thus models not grief’s transcendence but its navigation—learning to move with rather than past the dead we carry.

In constructing grief’s pedagogy without pretending to graduate from it, Ibemere creates space for readers to acknowledge their own ongoing education in loss. This is grief writing as ministry, offering not answers but presence, not solutions but honest companionship in the unknowing. The essay’s lasting achievement lies in making grief’s continuation—rather than its completion—the story worth telling.