SPECIAL REPORT: The hopes and hurdles of Niger State’s free maternal healthcare

A mother and her son at Kudu PHC, Niger State

By Anibe Idajili

The scorching heat of Niger State bears down on the Kudu Primary Health Centre (PHC) in Mokwa Local Government Area (LGA), but inside, 36-year-old Aisha Usman holds her baby close as she waits her turn for a routine antenatal checkup. For Aisha, the state government’s effort to eradicate maternal mortality through free healthcare is not just a policy but her reality.

“I am fortunate. Medical checkups and the child delivery have all been free for me and others who have enrolled,” Aisha confirms. Her experience is the good example of the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF)’s potential. The fund, designed to subsidize primary healthcare, removes the immediate financial barrier that often drives rural women to unqualified traditional birth attendants (TBAs).

But Aisha Usman’s story is closer to an exception than the rule. Across Niger State, the delivery of this life-saving fund is defined by bureaucratic delays, insufficient funds, exclusionary identification requirements, and entrenched cultural resistance.

In 2019, the Nigerian government launched the Basic Health Care Provision Fund (BHCPF) under Section 11 of the National Health Act (NHAct) 2014 to support the Basic Minimum Package of Health Services (BMPHS) and improve the overall financing of the health sector.

For a state like Niger, burdened by vast rural distances and poverty, this promise was monumental. But six years on, an investigation into the implementation of the BHCPF reveals that facilities offer zero-cost care one moment, only to turn away desperate mothers the next due to funding delays and bureaucratic identity requirements.

Niger State faces a high maternal mortality ratio, estimated at 130 per 100,000 live births. This figure significantly exceeds national averages and shows the peril faced by pregnant women who cannot access timely and adequate care.

Similarly, the under-5 child mortality rate in Niger State stands at approximately 103 deaths per 1,000 live births, meaning one in every seven children born in the state dies before their fifth birthday. The lack of consistent free antenatal care, safe delivery options, and post-natal services due to the BHCPF’s shortcomings directly impacts child survival.

Exclusion by Identification

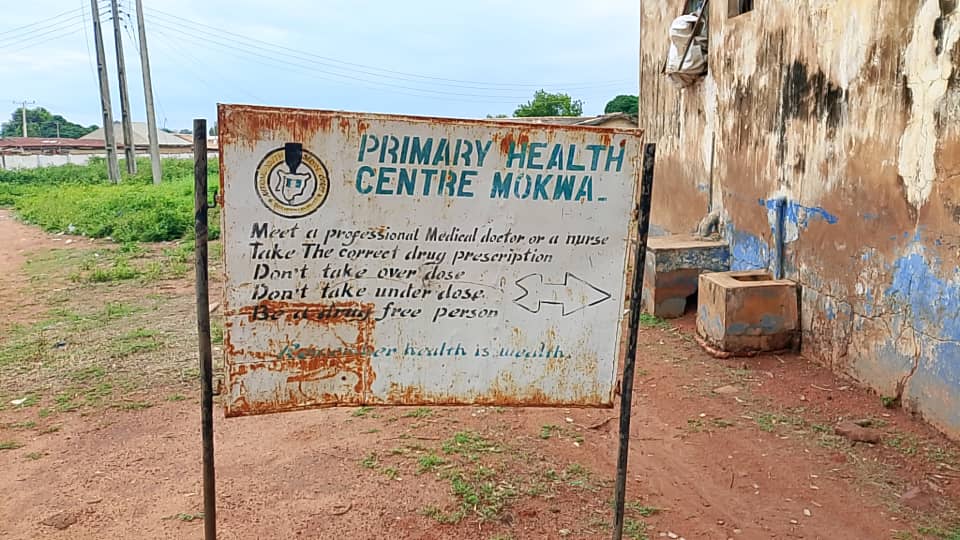

While Aisha Usman enjoys free care, just a few kilometers away in Mokwa town, Aisha Alhassan faces a different fate at the Mokwa Mother and Child Health (MCH)-PHC.

“I usually pay for every service,” Alhassan reveals. “I see other mothers being attended to for free, but they told me I must pay because I do not have a National Identity Number (NIN).”

This single requirement, the NIN, has become the gatekeeper to Niger State’s free basic healthcare. The BHCPF, the primary vehicle for federal funding channeled through the state, mandates enrollment using this National Identification Number.

This requirement keeps countless women from accessing care. Aisha Ahmed, Program Officer of the State BHCPF, however, reassures that “OICs (Officers in Charge) of PHCs know who to call when patients need to be enrolled. They have their contacts, so I do not know why this is an issue.”

At Kudu PHC, the Officer in Charge (OIC), Jubril Isah, confirms the administrative limits. He reports that only 137 of its 7,175 residents have been successfully enrolled under the BHCPF. While this small number of patients enjoys free care including antenatal, delivery, post-natal, and child immunization services, the cost for those outside the system is prohibitive.

Isah details the facility’s price structure for the excluded: “Pregnant mothers who are not enrolled pay ₦1,000 for the first antenatal visit and ₦500 for subsequent visits. For delivery, non-enrollees pay ₦2,000 for medications and consumables such as gloves, sanitary pads, and detergents.”

While these fees may seem small, in communities where disposable income is measured in daily subsistence, ₦2,000 can be the difference between choosing a supervised facility birth and resorting to a traditional home delivery, with its attendant risks.

The free care, where it works, has increased trust.

“The BHCPF has been very helpful,” Isah attests.

“We now have more community members visiting our facility since they have no reason to remain at home when sick.”

However, the facility’s reach is hobbled by the NIN requirement, forcing staff members to constantly sensitize residents to obtain the identifying documentation for the next enrollment window.

Delayed and Insufficient Funds

The most significant operational challenge is rooted in cash flow. The BHCPF funding, designed to be consistent, is anything but. This delay of funding starves the facilities, forcing PHC staff, who are instructed never to turn a patient away, to perform a constant balancing act between service delivery and solvency.

Following a referral from the Information Officer of the Niger State Primary Healthcare Development Agency, Fatima Mohammed, the reporter spoke with the State Program Officer for the BHCPF, Aisha Ahmed and presented her preliminary findings that disbursements to PHCs have been inconsistent and subject to significant delay. The Program Officer denied the claims.

“Disbursement is made in four quarters and has been consistent. The only thing PHCs can complain about is some little delay in disbursement, and that’s not our fault. We disbursed for all four quarters in 2024 to the 274 health facilities in the state. For 2025, we have only released funds for Quarters 1 & 2 and are working on Quarters 3 & 4,” Ahmed said.

She also highlights an incentive structure: “There’s a 2.0 clause on the way, where high-volume PHCs will receive ₦800,000 while low-volume ones will get ₦600,000. Facilities that meet all targets will receive an extra 10% funding.”

A look at Niger State’s 2023 approved budget shows that approximately 11.5% of its total budget was allocated to the Ministry of Primary Health. This figure, while a significant commitment, falls short of the Abuja Declaration benchmark of 15% of the total budget for health, a commitment made by African Union member states in 2001.

Mallam Mohammed A. Aliyu, the Ward Development Chairman of Mokwa Central Ward, agrees that “Funding for the BHCPF is sometimes delayed. It can take two to three months. So, providing free medications for the women who visit these PHCs can be sometimes difficult.”

This delay is prevalent across the state, from Mokwa LGA in the East Senatorial District to Kontagora LGA in the far North Senatorial District. At the Tundun Wada MCH clinic in Kontagora LGA, a designated BHCPF focal facility, a young mother named Hadiza lamented that her luck had run out.

“I enjoyed free healthcare before, but now I pay for it. The facility told us they simply do not have the required funds.”

A staff at Tundun Wada MHC confirmed Hadiza’s experience, stating that while the fund is helpful for medications and consumables, its sporadic nature is crippling.

“We are supposed to get ₦300,000 four times in a year. But it’s usually just once or twice in the first quarter or last quarter of a year. This year, we received just twice.”

In contrast, Mairo Abdullahi, the Focal Person at Kontagora Central PHC in the same LGA, reported a smoother experience, claiming her facility receives BHCPF funding quarterly and NiCare (Niger State Contributory Health Agency) funding monthly, and that both are regular. This suggests a disparity in logistics management or reporting across different focal facilities.

However, this investigation found out that, given the centralized nature of the federal and state disbursement channels, there is no administrative mechanism that would allow one designated BHCPF focal facility to receive consistent, scheduled payments while others in the immediate vicinity fail to receive any.

“We disburse the BHCPF to all facilities at the same time, and they all receive ₦300,000 each. There’s no way one facility will receive disbursement and another would not,” Ahmed, the State’s BHCPF Program Officer, claims.

Another challenge is the inadequacy of the funding when it finally arrives. Victoria Abubakar, the Officer in Charge of Mokwa Central PHC, clarifies the administrative constraints: “The ₦300,000 BHCPF disbursement has made our work easier but it is not always enough. Apart from maternal and child health, it has about 10 other approved uses. And there’s the issue of delay. It used to come quarterly, but now it’s in six months.”

Manpower, Distance, and Emergency

The BHCPF is designed to handle routine care. When complications arise, such as severe pre-eclampsia, hemorrhage, or obstructed labour, the PHCs must refer patients to higher-level facilities, usually General Hospitals. This is where the fragile system often crumbles entirely.

Nafisatu Musa, from Kwanti community, recounts her experience at Kpaki PHC. For 28-year-old Nafisat Musa from Kwanti community, the free care at Kpaki PHC had initially brought relief.

“My antenatal sessions were free, and the staff were kind,” she recounts. When she went into labour with her second child, she headed to the PHC, expecting a straightforward birth like her first. But this time was different. The baby wasn’t descending. The midwife on duty, after an examination, recognized the signs of obstructed labour and fetal distress. Nafisat needed an urgent Caesarean section, a procedure far beyond the scope of the Kpaki PHC.

“They told me I had to go to the General Hospital in Mokwa, about 30 minutes away,” Nafisat remembers. “My husband had no money for the transport, let alone the surgery. We thought we would lose the baby, or even me.” Her family had to scramble, borrowing from neighbours, before she could be rushed away in a borrowed vehicle. The surgery saved her and her baby, but the cost left her family in a financial situation, a contrast to the free care promised by the BHCPF.

Mohammed Jubril, the Ward Focal Person of Kpaki PHC, validates this fear, confirming the systemic failure that confronted Nafisat.

“One of the challenges we face is that the fund cannot cover serious pregnancy complications, and such patients may not have the finances to pay for medical care in the hospital we refer them to.”

The logistical hurdles are equally serious. Victoria Abubakar, the Officer in Charge of Mokwa Central PHC, notes the long distance between communities and referral centres: “The General Hospital and some referral facilities are a long distance from most people. Imagine travelling about 150 kilometres to get emergency medical care.”

Fatima Auwal, 32, a trader who delivered her fourth child at Kawo PHC, started hemorrhaging two hours after delivery. “The nurses stopped the bleeding initially, but they told me I needed a transfusion and specialist attention at Kontagora General Hospital. We had to borrow ₦15,000 just for the taxi, and when we arrived at the General Hospital, the free card meant nothing because the specialized procedures, they said, were not covered. We spent everything we owned to save my life. The free care at the PHC was a good start, but the referral nearly ruined us.”

In Kwanti, Hauwa Abdullahi’s baby was determined to be breech and she required an immediate Caesarean section at Mokwa General Hospital. “I was in serious pain, and my husband had to hire an old car,” Hauwa explains. “The car broke down twice. By the time we arrived, the baby was in severe distress. The medical team was able to save him but the distance and the fear that I would lose my baby before reaching help is something I will never forget.”

Coupled with the distance is a manpower shortage. Mohammed Aliyu Kimbokun, the Director of Primary Healthcare for Mokwa LGA, identifies personnel as a major problem.

“Until recently, we had retired midwives helping out under the Midwives Service Scheme (MSS), providing services in rural areas. But their one-year posting to PHCs has elapsed,” he explains.

To meet the needs of the local population and achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC), the minimum manpower standard, according to the National Primary Health Care Development Agency (NPHCDA), is that every PHC facility, regardless of location, is staffed with at least one medical doctor, 10 nurses, one pharmacist, three pharmacy technicians, two community health officers, six community health extension workers (CHEWS), one laboratory scientist, three laboratory technicians, one medical records officer, three medical records technicians, and one environmental health officer.

But, in reality, there is a manpower vacuum that leaves overburdened nurses juggling multiple roles.

At Kawo PHC in Kontagora LGA, a nurse asked: “A permanent doctor? We haven’t had one here as far as I know. We rely on referring patients out for levels of care that our current staff and limited equipment cannot provide.”

A health worker at Kudu PHC in Mokwa LGA also describes her daily struggle: “I often feel like I am three people in one. Serious cases often arrive too late and we can only offer basic healthcare before advising them to go to Mokwa General Hospital.”

“Even in the Mokwa General Hospital, there’s a shortage in manpower and doctors are overwhelmed with work. So, referring patients from PHCs there is still a challenge,” Kimbokun says.

Cultural Walls and Administrative Gaps

The struggle to deliver healthcare free of charge is not only financial or logistical. There are also cultural and administrative challenges.

The Ward Development Chairman of Kpaki/Takuma Ward, John D. Salau, has led community advocacy about the benefits of the BHCPF but faces stiff resistance on multiple fronts. He has organized numerous sensitisation drives for NIN registration, yet many community members remain negligent.

“One major excuse has always been distance, as some women come from surrounding villages to the PHC,” Salau notes.

More troubling is the patriarchal barrier:

“Also, some husbands do not allow their wives to go out to get their NIN or even visit the PHC for their healthcare needs.”

Mallam Mohammed A. Aliyu in Mokwa re-echoes this, also pointing to the negligence of mothers who are predominantly farmers and traders. They, he says, often prioritise their farms and businesses over visiting PHCs for antenatal sessions, leading to complications later.

Compounding this problem is the issue of administrative capacity among those managing the meagre funds. Hauwa Kulu Abdullahi, National Media Officer for the Federation of Muslim Women’s Associations in Nigeria (FOMWAN), highlights a lesser-known but key systemic fault.

“There is a lack of capacity with those administering the funds at PHCs, especially in preparing business plans and retirement of expenditures. This also result in delays in fund reimbursement,” Abdullahi explains. She notes that while NIN registration can be done on a mobile phone, many rural residents lack phones or the literary skills to operate them.

FOMWAN is actively working to bridge these gaps, conducting training for health workers and advocating for more women representation in Ward Development Committees (WDCs) because, as she puts it, “primary healthcare caters to vulnerable people such as women and children.”

The Stakes of Delay

Niger State’s commitment to free maternal health through the BHCPF and NiCare is a necessary intervention in a nation struggling with high maternal mortality rates. Data shows that subsidised care significantly reduces financial burden and increases facility usage, leading to better outcomes.

However, the current reality across Mokwa and Kontagora LGAs reveals a system perpetually on the brink of collapse, where the promise of ‘free’ is constantly undermined by the operational costs of delay, exclusion, and distance.

From the Kudu PHC, where only 137 residents are formally protected, to the mothers forced to travel 150 kilometres during an emergency, the common issue is inconsistency. The funds may come but they come late, are inadequate (covering only a fraction of the facility’s needs), and the eligibility requirements exclude those who need it most.

“We often advise PHCs to maximize the BHCPF by purchasing medications from the Drugs Management Agency in Minna before using the funds for other purposes,” Aisha Ahmed stresses.

But without consistent funding and wider NIN access, even the best policies cannot reach those who need them most.

The solution? Halima Sanni, a Program Officer at Youths in Justice Health and Sustainable Social Inclusion (YIJHSSI) says “We need faster, more reliable disbursements, simplified NIN enrollment, and stronger emergency referral systems at this point. Until then, the promise of free healthcare may remain unfulfilled for too many mothers in Niger State.”

For now, the hopes of free maternal healthcare under the BHCPF persist, but so do the hurdles.

This story was produced under the ICIR SPARK 2 Health Reporting Project supported by the International Budget Partnership (IBP)